These monks were Cau Dai Buddhists and their spiritual leader was a small, elf like man named the Dau Uhr or the Coconut Monk. The French had built him this monastery on the south end of a banana shaped island in the Mekong when they ruled Vietnam, then threw him in jail when he supported independence. The Communists in the north and the Americans in the south also invited him to taste their prison food. He said he was proud that he managed to be so honored by every occupying power.

Fall of 1970 found me in South Vietnam. After being “honorably discharged” from the Navy, I had moved back to Cambridge and became embroiled in the GI anti-war movement. Cafes in London, Paris and Toronto were full of American soldiers and civilian draftees who had chosen to “love it and leave it”. Talking with these men was very depressing because they believed that although they were safe from Vietnam they felt that they would never be able to return home again. Some ex-military friends and I decided to open a GI coffee house at a military base near Boston and offer free legal counseling. A friend of mine, Ann Singer, heiress of the Singer Sewing Machine fortune, funded this project.

Ann had been living in the Philippines during the early years of the Vietnam War and was married to an Air Force colonel flying illegal sorties over Cambodia and Laos, something that the State department fervently denied. She was outraged by what she saw and heard from her husband and wanted to fight back. One day she came to me with the idea of opening a law office in Saigon where we would offer to defend soldiers, free of charge, who were facing court martial for acts they had committed in the war. She asked me if I would help. We would use the courtroom as a bully pulpit to expose through the media the true human price we as a country were paying to continue this war.

Ann was now married to Martin Peretz, a Harvard professor and editor of Ramparts Magazine, a radical journal firmly opposed to Washington’s policies. She was friendly with many in the Washington legal community and was able to interest former US Attorney General Ramsey Clark to head up an impressive Board of Directors. We formed a non-profit corporation, The Lawyers Military Defense Committee, and began searching law schools for young and energetic attorneys ready and willing to move to a war zone. While Ann looked for staff, I headed to Vietnam to find office space and begin interviewing defendants.

I arrived at Tan San Ut Air Force Base early in the summer of 1970 accompanied by William Homans, a senior partner in a distinguished Boston law firm and from an even more distinguished old Boston family who had managed to “undistinguish” himself by joining the Chicago Eight defense team several years earlier. Bill was of my father’s generation and a bear of a man physically. Over six feet four at a stoop, his hand would grasp yours and bring tears to the eyes with its enthusiastic grip. Our first defendant was waiting for us 20 miles south in Long Binh Jail, the US Army’s largest prison in Vietnam and affectionately know to its inmates as “LBJ”.

On the day of my discharge from the Navy in Newport one year earlier, I had returned home to a joyful reception. My parents were glad I was not heading to jail myself or to war. One can only imagine their emotions when they learned that I had decided to head into the fray voluntarily. When they asked for an explanation, they exploded in frustration and anger before I could come up with an answer. Who did I think I was that I could play with the feelings of loved ones? Maybe being out of the limelight did not suite my ego needs? The truth was that I had no reasonable answer to why I was heading to Vietnam other than the fact that there were people suffering there and perhaps I could help. And I did have recent experience with military law.

My parents had always told me growing up that there was nothing I could not do with my life if I put my mind to it. They had imbued me with the courage to act on my convictions. They had sent me to the “best” schools where I learned to articulate my beliefs with confidence. Yet now when faced with their criticism, I was paralyzed. They joined me at Logan Airport in Boston to say good-by but as they hugged me their eyes said “how can you do this to us?”

The flight from Guam to Saigon was on a commercial United 727 and all the passengers were wearing civilian clothes. Walking down the stairs to the airbase runway I heard thunder in the distance rumbling in a cloudless tropical sky. My fellow travelers started running for the terminal but seeing no rain I slowed my pace. Then a stewardess jogged by and shot me a hard stare. “Get a move on pal” she said. “That's not thunder. We’re being mortared.”

And for just a moment I faltered, realizing for the first time that I was totally unprepared for a war zone. I had sat on rocks off the shore of Cohasset on cold November morning with a shotgun in my hand but never had ducks flying south for the winter been safer on their journey. Unlike most of my traveling companions, I would be unarmed as I made my way around Vietnam. I forced this realization down into the pit of my stomach and broke into a run.

Tyrone was black, from Alabama, lied about his 17 years of age to get into the Army and was up on charges of first degree murder. He was sitting in a cell by himself as I made my way the 17 miles south of Saigon for an interview. I had been in Vietnam two days.

“You’ve got a couple of ways you can get down there,” an Army sergeant told us at our hotel. “If you go by land, convoys leave twice a day from No Ba Trahn which is a cab ride from here. If you don’t get attacked you might make it in a few hours.”

“You can also take the air shuttle from the airport. That’s a 30 minute chopper ride.” We flipped a coin, Bill got the convoy, I got the chopper. We would compare notes.

Back at Than Son Uht Airbase I lined up with a motley crew waiting for a ride. Helicopters would appear like mid-west crop dusters, flying just above ground level at speeds of eighty to 100 miles an hour. They pulled up just short of the terminal building and hovered a few feet above the ground. A short line of soldiers stretched out onto the tarmac waiting to board. I was wearing a civilian shirt and army pants (they had more pockets for my pens, note pads and small camera) and my hair was definitely not regulation.

Standing in line in front of me was a character right out of Woodstock. Big Abbie Hoffman curls, blue jeans and Nixon printed on the back of his shirt. But he had replaced the “x” with a Nazi swastika. Before I got a closer look he picked up his gear and slowly began moving towards a recently arrived helicopter gunship.

A soldier at the door of the chopper wearing dark shades and a dirty green t-shirt held up three fingers. Abbie and I began running and an overweight colonel complete with jowls and a golf bag took up the rear. Abbie rammed his collection of cameras and lenses under his left arm, hopped up on the struts and was pulled aboard by “shades”. I was next and with two free arms climbed through the cabin door. I suddenly felt the chopper lift off the ground and looked back to see “shades” give the sweating colonel with the clubs the finger and slam shut the access door.

Abbie strapped himself into a passenger seat directly behind the pilot. I was just about to join him when the starboard gunner offered me his seat. No sooner had I straddled his 50 mm machine gun than his sweaty hands adjusted a set of headphones over my ears. All went silent except for a high pitched, barely audible whine of the rotors.

We rose up into the air and we were off like a rocket, flying parallel to the ground. No sooner would a grove of tall trees appear than we would gently lift up barely touching the top-most leaves. Then as if on cue my ears filled with the music of a most familiar song:

“You, who are on the road,

Must have a code that you can live by.

And so, become yourself,

Because the past is just a good-bye.

And you of tender years

Can't know the fears

That your elders grew by.

And so please help

Them with your youth

They seek the truth

Before they can die”

David Crosby and Neil Young had joined me for my ride in the starboard gunner’s bubble. Soon the sweet smell of weed drifted down to my outpost and gunner’s hand appeared bearing a gift. I respectfully declined and spent the next 14 minutes of the flight wondering what would happen if I just leaned back and pulled the trigger of the gun that rested calmly between my legs.

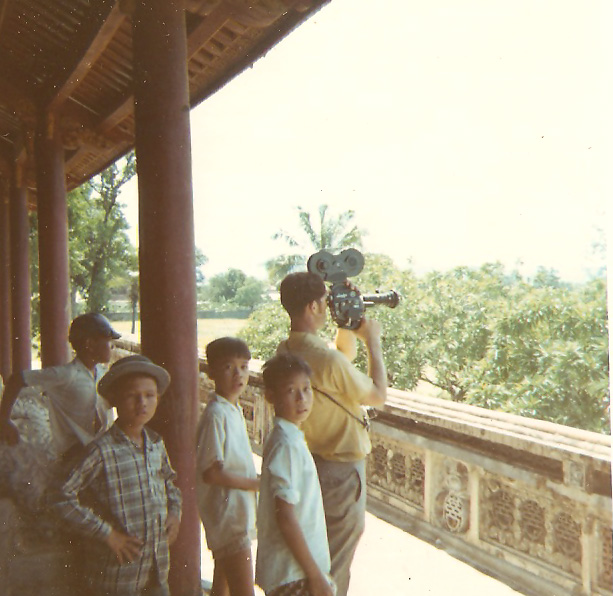

Abbie’s real name was Ed Razen and he worked for Dispatch News, a Bay Area wire service that supplied the alternative press with the “truth” about what was happening in Southeast Asia. He had worked as a CBS cameraman during the early days of the war until he parachuted onto a landmine. After a year of rehab at a clinic in New Haven, he returned to Vietnam wearing a different shirt, totally politicized by the anti-war movement he had discovered at Yale. After we arrived in Long Bin and I had interviewed Tyrone, Ed and I had a meal together and became friends. Several weeks later he invited me on a trip up the Mekong River. He was on assignment for French Television to make a film about the Coconut Monk and asked me to come along.

The B-52’s began their run after evening prayers. The bombs shattered the jungle on the distant shore and soon made their way out into the river, marching south like a giant underwater monster towards the monastery’s lighted towers. I watched the monks do some end of day chores and prepare for bed. I myself sat in a lotus position hoping to fool the gods that there were no Western skeptics on the island tonight. A bomb exploded in the mud not a football field away and I felt the floor under me shake. Then all was quiet. After what seemed a lifetime, the explosions skipped the island and continued marching on the river towards the opposite shore.

The night air was heavy and smelled of mud and rotting leaves. Telephone pole sized pilings held the monastery and the huts of the adjoining village over the Mekong as it flowed by underneath. Earlier in the day Ed and I had explored the small banana shaped inland attached to the north where the villagers used all available land to grow vegetables and fruits. “This is what Vietnam was like before the war,” said Ed.

I lay awake for hours on my straw mat, choosing to sleep under the stars and hoping to catch a stray breeze as it made its way down river. I was deeply shaken by the bombing raid and marveled that the island had been spared. I wondered if the pilots would return. A few monks attended to the prayer candles on the monastery’s alter whose centerpiece was a triptych icon depicting Buddha, Jesus and the Virgin all smiling at one another. Fish was cooking over a wood fire in the village and I felt a pang of hunger.

Sometime after midnight I heard a small engine pushing a dugout approach the island. I looked down to see four men in black pajamas stack their AK-47’s on the island’s dock and make their way up the path towards me.

“Bon soir” I said. I knew no Vietnamese and hoped that these guys might have picked up some French from their grandparents. “Bon soir” they replied. “Ou habitez vous?”

“Dans une petite ville pres de Boston”, I replied. “Ah, Boston!” they shouted with glee. “Red Socks, Red Socks”. Then they argued amongst themselves about who was going to win the World Series this year. I screwed up my courage and asked them where they were from.

“From a small town maybe 100 klicks north of Hue,” one of the older guys replied. The left side of my brain was rejoicing that we could share a common language and an interest in baseball when the right side of my brain started screaming that these four young men were North Vietnamese soldiers who I have been trained to fear and to kill in basic training. But before I could reach for the pen knife in my pocket one of the guys asked me if I had a girlfriend back home and did I have any photos. The best I could come up with was the picture of an old car my dad and I had restored. Well, they were ecstatic. They had never seen such a beautiful machine. I might as well have been standing in Tibet and showing a photo of the Dali Lama.

We talked all night and by dawn my new friends were gone. They were on a two-week leave from their platoon on the Laotian border and had chosen to venture into Vietnam to visit their spiritual leader, our host the Coconut Monk. These were the men I had been trainedto kill with my bayonet at close range. When I told them that I had been raised Catholic, they chuckled and confessed that they too had Catholic parents. But there had been a Cau Dai monk who lived in their village who believed in Buddha, Jesus and the Virgin Mary. This monk seemed to be happy every day, no matter what was happening, no matter the degree of suffering he underwent. He had told them about the Coconut Monk and they had risked their lives to spend one hour each for an audience. Though I would never see these men again, our meeting that night set in motion a journey that would consume the remainder of my life.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed