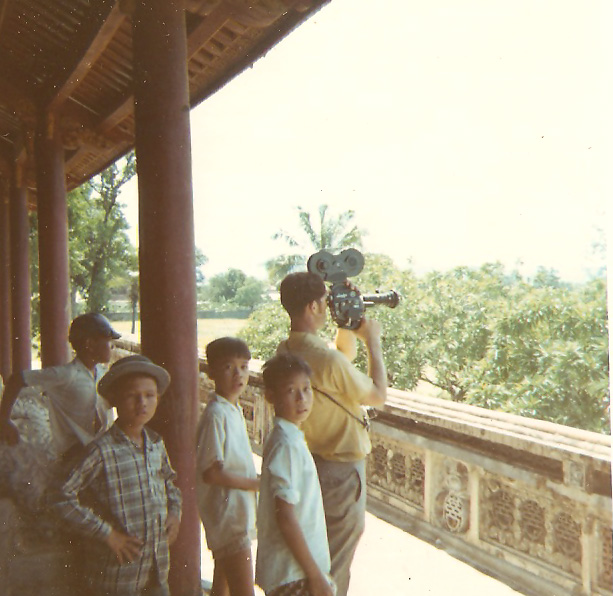

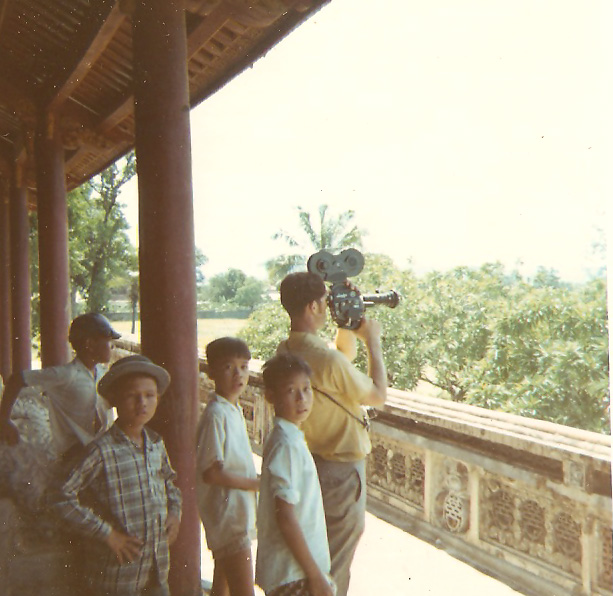

Ed Filming near the DMZ It was September and night came early in on the Mekong River. The monks finished their evening prayers and began replacing the Christmas tree lights that routinely burned out on the towers high above the pagoda. The evening breeze ruffled their brown robes as they efficiently moved above the ground on tall ladders. “It is necessary to have all the lights working so the bombers can see we are here,” a monk told me as he passed by. I pointed out to him the heavy cloud cover that was promising rain but he shrugged and said that God would protect them.

These monks were Cau Dai Buddhists and their spiritual leader was a small, elf like man named the Dau Uhr or the Coconut Monk. The French had built him this monastery on the south end of a banana shaped island in the Mekong when they ruled Vietnam, then threw him in jail when he supported independence. The Communists in the north and the Americans in the south also invited him to taste their prison food. He said he was proud that he managed to be so honored by every occupying power.

Fall of 1970 found me in South Vietnam. After being “honorably discharged” from the Navy, I had moved back to Cambridge and became embroiled in the GI anti-war movement. Cafes in London, Paris and Toronto were full of American soldiers and civilian draftees who had chosen to “love it and leave it”. Talking with these men was very depressing because they believed that although they were safe from Vietnam they felt that they would never be able to return home again. Some ex-military friends and I decided to open a GI coffee house at a military base near Boston and offer free legal counseling. A friend of mine, Ann Singer, heiress of the Singer Sewing Machine fortune, funded this project.

Ann had been living in the Philippines during the early years of the Vietnam War and was married to an Air Force colonel flying illegal sorties over Cambodia and Laos, something that the State department fervently denied. She was outraged by what she saw and heard from her husband and wanted to fight back. One day she came to me with the idea of opening a law office in Saigon where we would offer to defend soldiers, free of charge, who were facing court martial for acts they had committed in the war. She asked me if I would help. We would use the courtroom as a bully pulpit to expose through the media the true human price we as a country were paying to continue this war.

Ann was now married to Martin Peretz, a Harvard professor and editor of Ramparts Magazine, a radical journal firmly opposed to Washington’s policies. She was friendly with many in the Washington legal community and was able to interest former US Attorney General Ramsey Clark to head up an impressive Board of Directors. We formed a non-profit corporation, The Lawyers Military Defense Committee, and began searching law schools for young and energetic attorneys ready and willing to move to a war zone. While Ann looked for staff, I headed to Vietnam to find office space and begin interviewing defendants.

I arrived at Tan San Ut Air Force Base early in the summer of 1970 accompanied by William Homans, a senior partner in a distinguished Boston law firm and from an even more distinguished old Boston family who had managed to “undistinguish” himself by joining the Chicago Eight defense team several years earlier. Bill was of my father’s generation and a bear of a man physically. Over six feet four at a stoop, his hand would grasp yours and bring tears to the eyes with its enthusiastic grip. Our first defendant was waiting for us 20 miles south in Long Binh Jail, the US Army’s largest prison in Vietnam and affectionately know to its inmates as “LBJ”.

On the day of my discharge from the Navy in Newport one year earlier, I had returned home to a joyful reception. My parents were glad I was not heading to jail myself or to war. One can only imagine their emotions when they learned that I had decided to head into the fray voluntarily. When they asked for an explanation, they exploded in frustration and anger before I could come up with an answer. Who did I think I was that I could play with the feelings of loved ones? Maybe being out of the limelight did not suite my ego needs? The truth was that I had no reasonable answer to why I was heading to Vietnam other than the fact that there were people suffering there and perhaps I could help. And I did have recent experience with military law.

My parents had always told me growing up that there was nothing I could not do with my life if I put my mind to it. They had imbued me with the courage to act on my convictions. They had sent me to the “best” schools where I learned to articulate my beliefs with confidence. Yet now when faced with their criticism, I was paralyzed. They joined me at Logan Airport in Boston to say good-by but as they hugged me their eyes said “how can you do this to us?”

The flight from Guam to Saigon was on a commercial United 727 and all the passengers were wearing civilian clothes. Walking down the stairs to the airbase runway I heard thunder in the distance rumbling in a cloudless tropical sky. My fellow travelers started running for the terminal but seeing no rain I slowed my pace. Then a stewardess jogged by and shot me a hard stare. “Get a move on pal” she said. “That's not thunder. We’re being mortared.”

And for just a moment I faltered, realizing for the first time that I was totally unprepared for a war zone. I had sat on rocks off the shore of Cohasset on cold November morning with a shotgun in my hand but never had ducks flying south for the winter been safer on their journey. Unlike most of my traveling companions, I would be unarmed as I made my way around Vietnam. I forced this realization down into the pit of my stomach and broke into a run.

Tyrone was black, from Alabama, lied about his 17 years of age to get into the Army and was up on charges of first degree murder. He was sitting in a cell by himself as I made my way the 17 miles south of Saigon for an interview. I had been in Vietnam two days.

“You’ve got a couple of ways you can get down there,” an Army sergeant told us at our hotel. “If you go by land, convoys leave twice a day from No Ba Trahn which is a cab ride from here. If you don’t get attacked you might make it in a few hours.”

“You can also take the air shuttle from the airport. That’s a 30 minute chopper ride.” We flipped a coin, Bill got the convoy, I got the chopper. We would compare notes.

Back at Than Son Uht Airbase I lined up with a motley crew waiting for a ride. Helicopters would appear like mid-west crop dusters, flying just above ground level at speeds of eighty to 100 miles an hour. They pulled up just short of the terminal building and hovered a few feet above the ground. A short line of soldiers stretched out onto the tarmac waiting to board. I was wearing a civilian shirt and army pants (they had more pockets for my pens, note pads and small camera) and my hair was definitely not regulation.

Standing in line in front of me was a character right out of Woodstock. Big Abbie Hoffman curls, blue jeans and Nixon printed on the back of his shirt. But he had replaced the “x” with a Nazi swastika. Before I got a closer look he picked up his gear and slowly began moving towards a recently arrived helicopter gunship.

A soldier at the door of the chopper wearing dark shades and a dirty green t-shirt held up three fingers. Abbie and I began running and an overweight colonel complete with jowls and a golf bag took up the rear. Abbie rammed his collection of cameras and lenses under his left arm, hopped up on the struts and was pulled aboard by “shades”. I was next and with two free arms climbed through the cabin door. I suddenly felt the chopper lift off the ground and looked back to see “shades” give the sweating colonel with the clubs the finger and slam shut the access door.

Abbie strapped himself into a passenger seat directly behind the pilot. I was just about to join him when the starboard gunner offered me his seat. No sooner had I straddled his 50 mm machine gun than his sweaty hands adjusted a set of headphones over my ears. All went silent except for a high pitched, barely audible whine of the rotors.

We rose up into the air and we were off like a rocket, flying parallel to the ground. No sooner would a grove of tall trees appear than we would gently lift up barely touching the top-most leaves. Then as if on cue my ears filled with the music of a most familiar song:

“You, who are on the road,

Must have a code that you can live by.

And so, become yourself,

Because the past is just a good-bye.

And you of tender years

Can't know the fears

That your elders grew by.

And so please help

Them with your youth

They seek the truth

Before they can die”

David Crosby and Neil Young had joined me for my ride in the starboard gunner’s bubble. Soon the sweet smell of weed drifted down to my outpost and gunner’s hand appeared bearing a gift. I respectfully declined and spent the next 14 minutes of the flight wondering what would happen if I just leaned back and pulled the trigger of the gun that rested calmly between my legs.

Abbie’s real name was Ed Razen and he worked for Dispatch News, a Bay Area wire service that supplied the alternative press with the “truth” about what was happening in Southeast Asia. He had worked as a CBS cameraman during the early days of the war until he parachuted onto a landmine. After a year of rehab at a clinic in New Haven, he returned to Vietnam wearing a different shirt, totally politicized by the anti-war movement he had discovered at Yale. After we arrived in Long Bin and I had interviewed Tyrone, Ed and I had a meal together and became friends. Several weeks later he invited me on a trip up the Mekong River. He was on assignment for French Television to make a film about the Coconut Monk and asked me to come along.

The B-52’s began their run after evening prayers. The bombs shattered the jungle on the distant shore and soon made their way out into the river, marching south like a giant underwater monster towards the monastery’s lighted towers. I watched the monks do some end of day chores and prepare for bed. I myself sat in a lotus position hoping to fool the gods that there were no Western skeptics on the island tonight. A bomb exploded in the mud not a football field away and I felt the floor under me shake. Then all was quiet. After what seemed a lifetime, the explosions skipped the island and continued marching on the river towards the opposite shore.

The night air was heavy and smelled of mud and rotting leaves. Telephone pole sized pilings held the monastery and the huts of the adjoining village over the Mekong as it flowed by underneath. Earlier in the day Ed and I had explored the small banana shaped inland attached to the north where the villagers used all available land to grow vegetables and fruits. “This is what Vietnam was like before the war,” said Ed.

I lay awake for hours on my straw mat, choosing to sleep under the stars and hoping to catch a stray breeze as it made its way down river. I was deeply shaken by the bombing raid and marveled that the island had been spared. I wondered if the pilots would return. A few monks attended to the prayer candles on the monastery’s alter whose centerpiece was a triptych icon depicting Buddha, Jesus and the Virgin all smiling at one another. Fish was cooking over a wood fire in the village and I felt a pang of hunger.

Sometime after midnight I heard a small engine pushing a dugout approach the island. I looked down to see four men in black pajamas stack their AK-47’s on the island’s dock and make their way up the path towards me.

“Bon soir” I said. I knew no Vietnamese and hoped that these guys might have picked up some French from their grandparents. “Bon soir” they replied. “Ou habitez vous?”

“Dans une petite ville pres de Boston”, I replied. “Ah, Boston!” they shouted with glee. “Red Socks, Red Socks”. Then they argued amongst themselves about who was going to win the World Series this year. I screwed up my courage and asked them where they were from.

“From a small town maybe 100 klicks north of Hue,” one of the older guys replied. The left side of my brain was rejoicing that we could share a common language and an interest in baseball when the right side of my brain started screaming that these four young men were North Vietnamese soldiers who I have been trained to fear and to kill in basic training. But before I could reach for the pen knife in my pocket one of the guys asked me if I had a girlfriend back home and did I have any photos. The best I could come up with was the picture of an old car my dad and I had restored. Well, they were ecstatic. They had never seen such a beautiful machine. I might as well have been standing in Tibet and showing a photo of the Dali Lama.

We talked all night and by dawn my new friends were gone. They were on a two-week leave from their platoon on the Laotian border and had chosen to venture into Vietnam to visit their spiritual leader, our host the Coconut Monk. These were the men I had been trainedto kill with my bayonet at close range. When I told them that I had been raised Catholic, they chuckled and confessed that they too had Catholic parents. But there had been a Cau Dai monk who lived in their village who believed in Buddha, Jesus and the Virgin Mary. This monk seemed to be happy every day, no matter what was happening, no matter the degree of suffering he underwent. He had told them about the Coconut Monk and they had risked their lives to spend one hour each for an audience. Though I would never see these men again, our meeting that night set in motion a journey that would consume the remainder of my life.

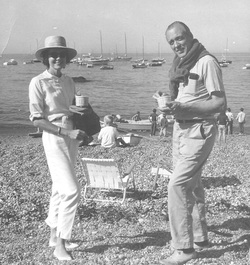

My father loved designing and sailing boats that moved quickly over the water. Our home was next to the ocean and that was as close as my mother wanted to get to being on the water. So it was a memorable occasion the day my dad coaxed her out for a picnic lunch on our sailboat that he had designed and built. A brisk wind took us to the Boston Lightship five miles out from shore. It was a hot summer day and the sea was as still as a mill pond and by noon every breath of wind had vanished.

“Well, Frannie, now what?” Mom asked. “No problem,” replied my dad. “By the time we finish our picnic the afternoon wind will come to take us home”. I looked overboard and imagined myself with my mask and flippers on, floating on the surface and looking down toward darkness and the bottom 200 feet below. No matter how deep I would dive I would never see the ocean floor, only sunlight disappearing into a void where I knew all the monsters of the deep lived.

Most summer mornings I would get up, throw on an old swim suit and head out to the rocks in front of my house where I would either dive for lobsters which we would eat for lunch or spear flounder which mom would clean for supper. The water was mostly shallow, barely over my head and mom could keep an eye on me from the house as she did her chores. I devoured books by the French diver Jacques Cousteau and my dad and I made a rubber diving suit one summer to keep me warm against the cold currents. Off my house I was always able to see the bottom and felt safe from the larger fish that I imagined swam out in the deeper water.

The lightship was very close now and I waved at a Coast Guard sailor walking on deck. As mom was taking the lunch out of the picnic basket my brother John tapped me on the shoulder. Off the port bow of our sailboat appeared the fin of a fish that we both immediately recognized as belonging to a shark. We both looked at each other with concern. This was the last thing mom needed before lunch. She was dressed in her funny bathing suit and huge sun hat happily eating a tomato sandwich and looking in the opposite direction.

Just as I was about to covertly signal my dad, another fin appeared off the port stern and all at once I realized that it belonged to the same fish, that it was in fact not a fin but part of a tail. This meant that the shark was as long as the boat, 18 feet overall. We were having lunch with a monster from the deep, a hammerhead shark. I tried to think of some clever way to introduce our predicament to my mom who was well known for her ability to overreact.

“Hey guys, look who has dropped by to say hello.” Mom nonchalantly looked over her left shoulder at the front fin, then over her right shoulder at the tail fin and then said with uncharacteristic bravado, “Oh darn, just when I was thinking of taking a dip.”

But today my mother was no longer alive and this morning I would help bury her. I sat in the upper most room of my childhood friend Michael’s home. No one lived up here now. Once it had been the secret domain of one of his children. Built like the upper room of a lighthouse with windows facing the sea, one could see the distant beach and the breaking waves. This morning I was not looking out the windows. My eyes were shut and I was as still as a post as my mind was busy at work feeding me the raw footage of a small child playing by the ocean, a doting mother by his side.

I had awakened early to prepare for the eulogy the oldest son must give. I went over my notes but my words fought with my conscience. Since she arrived in Cohasset as the young bride of my father almost 70 years ago, my mother had been the pinnacle of our community. For days now, many people whom I had not seen in over 50 years had been writing, calling, or stopping me in the street. Their eyes and their voices filled with tears as they shared with me stories of my mother’s kindness, courage and strength.

And I would leave these exchanges asking myself if they were talking about my mother or someone else. As I now sat rigidly in the tower room, the movie house of my mind played and replayed in vivid color the stories I held to be true.

The series of telephone calls to my college dorm room would usually start on Wednesday evenings. My father would be first, asking how things were going this week and did I have any plans for the weekend. I would reply that school was fine, that I might make the second string soccer squad and that I had plans to visit friends on the Cape after Saturday’s game. Mom’s call would follow Thursday night, saying that she had just bought a roast at the Central Market and why don’t I bring my friends home for the weekend. I would tell her patiently that I had plans and wish her well. Dad would end the week with a pleading tone in his voice, saying without a word that I was needed at home.

And I always went home. And my mother and I would always end the weekend with a fight. And I would pull my car over every Sunday evening at the same stretch of deserted road two miles from home and wretch my guts out in the ditch. Only then would tears appear in my eyes.

My mom grew up in the Boston suburb of Newton in the roaring 20’s. She was the oldest of five and the apple of her fathers’ eye. She never recovered completely from his sudden death, leaving her when she was only 17 years old. She became a kindergarten teacher and fell in love with my father the day he arrived at her classroom with two newborn baby spring lambs. My dad’s mom Josephine invited them shortly after their marriage to join her on the rocky shores of Cohasset south of Boston and purchased for them a huge Spanish stucco home overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. Complete with red tile roof and porches reaching out over the sea, parakeets escaping from a nearby amusement park would routinely mistake our house for the coast of Mexico and make their home for the summer.

My dad was born in the Dorchester section of Boston where thousands of Irish families had settled since the mass immigration of the mid 1800’s, victims of genocide at the hands of the British and the potato famine. His father John was a liquor salesman, a sports guide in the North Woods and could barely write his name. Frannie never talked much about his youth. His father died when my dad was 7, leaving Josephine to raise he and his two brothers, John Jr. and Robert. In spite of his refusal to talk of the past I did learn a few things.

One day Marty and I attended a wedding in Vermont on a beautiful hillside under a green tent. Back in the corner sitting all by himself was a rugged gentleman who looked like someone’s grandpa. I didn’t know anyone at the wedding so I sat down beside him and introduced myself.

“I once knew a John Hagerty,” Norm said. “He was from Boston.”

“Oh, that must be my brother,” I replied.

“This John Hagerty has been dead for a long time,” he said.

I quickly realized that he might be talking about my grandfather.

“He was quite a character. He used to take “sports” hunting in the North Woods and one fall he took my dad and me to Quebec to hunt moose. Two things I remember were that he always wore just a flannel shirt, rarely a jacket, no matter how cold it got. And he could throw a knife.”

“One day we were camped about 200 miles north of Montreal. We were dropped off by the train and had enough grub for one week. He had an Indian for a guide and we made camp on a lake. Well sure enough there we meet another bunch of sports who were fishing and they also had an Indian guide from the same tribe.”

“Well we sort of camped together, had two separate fires. And pretty soon this guy from Colorado comes over and says to John ‘I hear you’re pretty good with a knife.’ John doesn’t say much. ‘My guide says that you can throw a knife through a pack of Lucky Strikes at 50 paces.’ John grunts something and the guy throws down $20 that says he can’t.”

John’s Indian takes out a pack of Lucky Strikes, walks out 50 paces and lays the cigarettes on a tree branch. John then gets up slowly, reaches in his pocket and covers the Colorado guys bet, and without so much as an aim, whips his long knife out of his leather sheath and through the air and splits the pack in two. Later he gave both Indians a $10 bill on the sly.”

This story reminded me of a day in Dorchester looking for an old car with my dad. We were driving down a street when he casually pointed out the house where he was born. I forced him to stop the car and I jumped out and ran up the driveway and knocked on the front door. He was so embarrassed when the owner and his wife invited us in. But they took us down cellar and showed me the beam filled with knife marks. My grandpa had died here from a massive coronary at the young age of 37.

Thought Josephine would mourn his death for the remainder of her life, a bright light of intellectuality and financial acumen accompanied her wherever she went. From her business dealings she amassed enough money to send both Robert and John to Harvard and my dad to MIT. Through her son John she made the acquaintance of the German architects Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer and the Dutch designer Meis Van Der Rough. These three architects had fled the Bauhaus School of Design as the Nazis took over Germany. Together they agreed to design for Josephine their first residential home in America, complete with Bauhaus furniture. We called the place “the modern house”. Every summer of my childhood I would run down the back stairs of my Spanish “hacienda” and join Josephine in her Bauhaus garden of sunflowers to eat honey she would import from Cuba with large wooden spoons.

My grandmother outweighed my mother by 100 lbs but they quickly became fast friends. They cut quite a path as they made their way down Cohasset’s Main Street towards the Central Market to go shopping. Mary in her summer dress with me riding inside her belly waiting to pop out and huge Josephine dressed in a widow’s black, defying the July heat wave that summer. Men would tip their hats and women would smile as they passed, perhaps slightly intimidated by the confidence Josephine exuded as she made her way through town.

Our neighbors were almost all of old Yankee stock and when my father applied to join the Cohasset Yacht Club he wondered out loud if he had a chance. But by then he was already a talented boat builder and some of the yacht club members had rowed in his sleek racing shells at Harvard so he and my mom were admitted.

“You know Mary,” she said one day “when I graduated from Radcliffe in 1907, I was the first Irish girl ever to do so. But I could not find a job. My name was Curry and everyone knew I was Irish. The newspapers routinely ran ads for help adding ‘Irish need not apply’. But we survived and so will you. These people will learn to love you, you mark my words.”

The first and only time I saw my mother and father cry together was the morning we found Josephine dead in the modern house. Only a few days before I had been visiting after school and found her working with Gropius and Van Der Rough, discussing a rusted window frame. There was an artist there that day painting with pastels on the stairwell walls named Alfonso Ossorio. He believed he was the reincarnation of St. Francis of Assisi. Dressed in monk’s habit, he chewed peyote nuts he carried in the deep pockets of his robes and recited prayers in Mexican Spanish.

It was 4:30 in the afternoon when Cardinal Cushing came on the radio to say the rosary. Everyone knew the drill. Jew, Lutheran, stoned out monk or child, we all stopped our work and either knelt or sat. And under the watchful gaze of our hostess we respectfully submitted to the drone of the Cardinal’s nasal voice. “Glory be to the faatha, son and holy ghost…..” When Josephine died the following day my mother lost a strong ally and friend and she wondered aloud if she could survive without her by her side. Now my mother was gone and it was my task to write her epitaph.

As I sat in the attic room of Michael's room I recalled one story I had recently heard just the day before. It came from a man named Paul, a rough and tumble kind of guy whom I would not normally associate with my mom. Paul and a group of his friends wanted to have a party and campfire on Sandy Beach but the police would not allow it. There was a summer curfew in place. No one was allowed on the beach after 10. Paul told me he had somehow run into my mom downtown and when she learned of his problem, offered our small, private section of Sandy Beach for his friends.

“I was amazed in a way that I felt comfortable even asking her,” Paul told me. “I really didn’t know her all that well. I think I did some landscaping work for your family. In any case she came down to the beach after the party started to ask if we needed anything. She offered the girls to use the bathroom in your house. Everyone was very touched by her kindness. That night we had a pretty rowdy crowd. We drank some but no fights. Somehow everyone stayed very mellow, in respect for your mom and her kindness.”

The day Marty and I were married was a hard one for my mom. Instead of a church, she was sitting on a hay bale in a two hundred year old barn. Instead of "Ave Maria" we were singing folk songs. On the way back to Boston that night she told my brother John that "it would have been better if he had died in Vietnam." But of course she loved Marty, softened over time and would die again if she knew I was aware of what she said. But a son tends to carry something like that around for a while. Paul's comment reminded me that she could on occasion be comfortable and engaging with my friends. For one moment I really could see her on our beach with these young folks, shaking hands with the boys and their dates, some of whose parents worked in Dad’s factory. I saw her for a moment as vulnerable, reaching out not as the queen on the ocean but as the mother of two boys who themselves might someday be looking for a safe place to have a campfire and a beer with some friends. Lifelong judgments suddenly took a back seat and tears fell for the first time since her death.

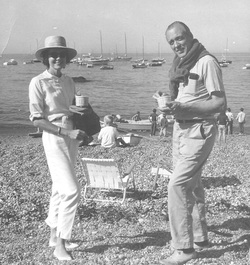

Mom and Dad

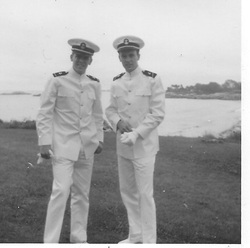

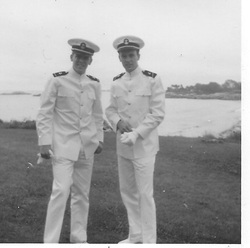

Peter and Brother John in dress whites

Cohasset, 1968

"Family Fun Day” the poster read. “Come meet Secretary of the Navy John Chafee. Games for the children, free food.” It was fall, the trees were turning in Rhode Island and someone nearby was burning leaves. The Lloyd Thomas had set sail two weeks before for Vietnam. Lowell had me transferred to a destroyer tender, a huge floating repair vessel. I was ironically assigned to assist the ship’s Chaplain with the spiritual issues of his crew.

To this day I cannot remember saying good-by to any of my shipmates. Another officer on board, Lt. Henry, had taken over command of Deck Division. None of my men were watching as their unconventional leader walked away for the last time. All I can remember was deciding not to throw my hat in the water as I left.

But as the Lloyd Thomas headed for the Pacific, things started coming apart. Lt. Jay and two other division officers on board decided to leave the Navy and all three handed in their commissions on the same day in protest. Several men in my division had caught wind that I was leaving because of some fallout with the Captain. Lowell and I had discussed the risk of informing my men of the dangers they faced going to war on an unfit ship. If any of them went ‘over the hill’ before the ship sailed, I would be open to charges of encouraging desertion in the face of combat. This would undoubtedly complicate Lowell’s defense efforts.

Yet to just leave saying nothing seemed cowardly and irresponsible. So one evening before my final departure, I was standing watch with my 3rd class petty officer, Pomerantz. An affable young man from Boston, he could easily have been a friend in civilian life. Over the year I had spent with my men, I found that they were very uncomfortable with any conversation that strayed from the clearly defined role of officer and enlisted man.

But Pomerantz was different. He had been on deck the day the MP’s came for me. He appreciated the nuances of surviving military life in the late 1960’s. So one night I chose to tell him what was up with the forward gun mount. His combat station was in the powder room that supplied the gun with shells. He would be directly in harm’s way should an accident occur. He listened intently, saying nothing. I learned later that six men on the Lloyd Thomas went missing when the ship sailed from San Diego for the South China Sea.

Now at Family Fun Day I had a chance to see the Secretary of the Navy in person, up close. The event was held in a large aircraft hangar. Tables of food lined the sides and proud sailors dressed in their finest uniforms paraded their families about till they found a seat. First some marching bands warmed up the crowd. Like church, no one sat in the front row so I made my way there and sat down. Before anyone noticed, a tall, distinguished man with grey hair and dressed in civilian clothing came ambling out a side door and started greeting the sailors, their wives and their children. People began flocking to him like a trout to a fly. He hunkered down to chat with four year olds, taking up to several minutes listening to these kids. I remembered that he had once been a popular Rhode Island Senator and had been considered a political moderate. Finally he made his way to the microphone and began to speak.

Short of an opening welcome, I remember nothing of the specifics of his talk. It was not long, maybe ten minutes. What I will never forget is how his talk ended.

“I have come here today to hear from you about your concerns. We live in the same state and we have all chosen to serve our country in its time of need. So we are literally one family here today. I have asked that microphones be placed throughout the hall. Please raise your hand and someone from my staff will accompany you to a podium from which we may speak to one another”.

I was stunned. Here was the man who needed to hear my story and today he had unknowingly made that conversation possible. All I had to do was raise my hand.

It took a while for the room to quiet down. Someone had said there were 4000 people there yet no hands were raised. The room grew silent. Rather than start talking again, John Chafee smiled and remained quiet. He would wait because he knew that this part of his family was not used to standing up and saying what was on their minds.

Finally one sailor raised his hand. His question was followed by one from a Navy wife. I watched my right hand lay on my leg, frozen, unable to move. My mind listed all the reasons why I should not take action. Here was our leader, a compassionate man trying to make the lives of these families a bit lighter if for only a moment. Many of these men were on their way to war. Some had just come back. This was the real world. What right did I have to interject my own personal drama into these proceedings?

I watched as a drum and bugle corps assembled off stage preparing to say good-by to the Secretary. Chafee was reaching for his closing notes. Before I could stop myself, I was on my feet. “Sir”, I cried too loudly. “Do you have time for one last question?”

Chafee put his papers aside, adjusted his spectacles and looked down at the first row. What he saw was a young officer in summer whites, white shoes, white socks, white pants, white shirt holding a white hat in his trembling hands.

“Please,” said Chafee, pointing me to a nearby microphone. I can only imagine a Marine Corps colonel somewhere in the room stop chewing his overcooked hamburger and slowly turning his face towards the front of the hall. “Take your time. This is your day,” Chaffee said

“Mr. Secretary,” I began, “thank you for coming to Newport today and offering us an opportunity to speak to the difficult issues that face us as members of the United States Armed Forces. Thank you in advance for addressing my question. If a member of your Navy finds something wrong that could result in the injury or death of a fellow crew member and he reports this finding to his superior officer and this superior not only fails to acknowledge the problem but in fact punishes this sailor, what would you do, if anything, in response?”

Time now stood still. For better or worse I had said my piece. Where others had sat down after delivering their question I remained standing. Chafee looked at me and understood that what hung between us now was not a question but a statement. A statement given with respect but one with implications that reached far beyond the walls of this hanger.

“Thank you for your thoughtful question Mr….”

“Hagerty, Ensin Hagerty; U.S. Naval Reserve 0105-289-70524”.

“Thank you Mr. Hagerty, I will have my staff look into the specifics of your question immediately after this meeting. But in practice the Navy will not tolerate information being withheld for whatever reason if it endangers the life or well-being of its members”.

“Thank you, sir,” I said and without thinking I turned, left the microphone and walked out of the hanger. There was already a crowd in the parking lot heading home so I jogged for my car and left the scene as quickly as possible Three days later Lowell called with the news. I had been honorably discharged from the US Navy, effective immediately. The following day I was a civilian.

Mornings on the LLoyd Thomas were the worst. I would wake up and remember what was going on and I would put the pillow on my head and refuse to rise. Several times Lowell would call early just to make sure I was up and would make the officers’ morning staff meeting. “We can get through this,” he would say in his boyish, mid-west optimism. Lowell was Lutheran and he had faith.

One Saturday in late summer he called and in a soft voice asked, “Can you get down here? I think that I have found our man.” When I arrived we were the only folks at the JAG office but even so Lowell closed the door behind me after I entered.

“I hired a local civilian lawyer friend of mine to do some snooping. Sometimes they can open drawers we can’t. Well my friend tells me that there is a Marine Corps colonel in the Secretary of the Navy’s office who has it in for you. This is too bad because John Chafee, who is the Secretary, is a pretty decent guy and might side with us on this. But this Marine has put your file in a very dark place where it will not see the light of day. Our colonel is banking on you cracking, doing something drastic like leaving the country.

I smiled at the memory of my last overseas trip. It was Easter past, I’d been slipping in the ‘faith’ department and took two weeks leave that I had coming. It was completely illegal for an active duty military person to leave the continental US without permission but I just boarded a flight in civilian clothes from Boston to London and moved into a friend’s flat in Cadogan Square. I had been an exchange student here in the early 60’s and wanted to see if I could live in exile in my old stomping grounds.

I visited pubs and coffeehouses where American GI’s who were now deserters enjoyed celebrity status from the Beattles generation. Men with pony tails and women with nipples popping through their blouses would buy these American GI’s pints of lager beer, praising them for their courage but expecting graphic depictions of the blood, carnage and rape in return. Where these Brits saw courage, I saw fear. I had planned to sit and talk with these soldiers but in the end I could not.

On Good Friday I went to Westminster Cathedral and sat in the front row, the very seat I had occupied just seven years before when I was at a school down the road. For the first time I began to appreciate the sacrifice that Jesus made. He believed in something and was willing to die for it. In my mind, Easter Sunday paled in comparison. As I made my way through the streets of London that night, I realized with certainty that my battle would be fought at home, not in some far off British pub or Parisian coffeehouse.

Lowell politely cleared his throat. “So Pete, you need to live a squeaky clean life now. Stay close to here. No speeding tickets, no bar fights. Don’t provide them with an excuse. We need to find a way to get your file back out in the open. We need some time.”

I was now living with another officer from our ship in a small apartment in Newport. It was the summer of Woodstock, of Joan Baez marrying David Harris and it seemed that revolution was in the air. One night I felt this overwhelming need to see my parents. They lived two hours away and were having some problems of their own and I needed to check in.

Cohasset’s postmaster, Gerard Keating, had lost his son in Vietnam. Word had finally reached home of my provocative actions in the Navy and now people were avoiding my parents in public. Gerard and my father had worked side- by- side posting my families’ business mail every day for over 20 years and now Gerard refused to look at dad in the face. My mother was in the Central Market when a longtime friend refused to talk to her. I learned all this from my brother John. They were not about to burden me with their own issues.

So failing to heed Lowell’s advice, I headed off the base, changed at the apartment into civilian clothes, and watched in the rear view mirror for an escort as I traveled the back roads into Massachusetts. It was a gorgeous late summer sunset that greeted my arrival home and after saying hello to my surprised folks I went for a swim. Mom cooked up some fish and we sat on the porch, catching up with our respective news. It had been months since I had seen them. Dad said that he had watched the Lloyd Thomas sail by Minot’s Light on its way south to Newport. We were staying away from all the difficult stuff when the phone rang and dad went to answer it.

“Hello, is this the Hagerty residence?”

“Yes,” replied my father.

“Mr. Hagerty, my name in Hines, John Hines and I am a Military Police officer stationed at the Naval Base here in Boston. If you are Francis, then perhaps I was a neighbor of yours growing up on Hillside Ave. in Dorchester. “

“Yes, I remember your older sister Joan,” replies my father.

“Mr. Hagerty, we have reason to believe that your son is visiting you there this evening. Is that true?”

“Yes, we are just finishing supper”.

“Well, I am afraid to report that there are two MP’s coming down there to arrest your son.”

“Why?”

“The charge is that he is Absent Without Leave from his base in Newport.”

“But my son is off tonight and chose to come here to have supper with my wife and me and will return to the base by morning. Officer Hines, why are you calling me and telling me all this?”

“I recognized the name and as a courtesy I am giving you a heads up.”

“Well, Officer Hines, my son has done nothing wrong. And if your associates are coming here to arrest him, you tell them to be sure to bring two sets of handcuffs”. My father then hung up the phone and stood looking at the floor.

Both my parents were Republicans. My father used to joke that if they were Democrats then the fire department might not come if his factory caught on fire. I had never seen my parents stand up against authority. Tonight my dad said that he was going to jail with me.

My mother began chattering, then screaming, then moaning. She walked the hallways of our house cursing me. My dad excused himself, went up and lay down on his bed and began having mild chest pains.

Mom took some Valium and I went to sit on my dad’s bed. I wanted to tell him how proud I was of what he had done. He had come to my rescue like I had always hoped he might. Instead I asked him for a story.

As a child, every night he would treat me to the adventures of Robin Hood and Sherwood Forest. So this night, as we awaited our jailers, he transported me back to a forest clearing where Friar Tuck was battling the Sheriff of Nottingham with a large pole while Robin Hood once again escaped to be with Maid Marion. As the words rolled out his breathing eased and when the story ended, he fell into a deep sleep.

Sitting by his side I felt totally responsible for my parent’s trauma. When will I be able to make decisions in my life and not feel the weight of responsibility for others? Where does their life end and mine begin? I would not come close to answering this question until the day I had my own family.

I waited until 2 am but the MP’s never came. I never knew if it was a bluff or whether the Navy was not prepared for the arrest of a 42-year-old father of two. I have always preferred the latter. Years later at my Harvard 25th reunion I told this story of my father’s courage to 800 of my returning classmates and it brought the house down. It seems that many in the room had desperately wanted this kind of support from their own parents but it was not to be. That summer night I had seen my father face fear head on and not turn and run. For this I would love him forever.

The cold, June sky was a cobalt blue and steam shot from the horses’ nostrils as they moved across the chest high field of hay. It was our first summer in Maine and Barney and Nicker were pulling a #9 McCormick Dearing High gear horse drawn mowing machine that Bob and I had found and fixed up. Other than the early morning birds the only sound was the cutter bar as it neatly clipped the tall timothy and orchard grass and laid it in long neat rows behind the mower. Our friend Wayne whose farm we were haying walked along nearby giving us pointers.

Coming to Maine in the early 70’s Marty and I were part of a “back to the land” movement where suburban young adults tired of the lives their parents were living and weary of the Vietnam War voted with their feet and left their college diplomas for the organic gardens and simpler lifestyle of rural America. The small farm Marty and I found was built somewhere around 1840 and had provided six generations of families with a subsistence existence. These folks would plant a garden in the spring, cut hay in the summer, harvest crops and spread manure in the fall, log in the winter and start all over again in the spring. When we moved in, our farm had a stall for two big horses and tie up for three cows, one for milk and two for meat. Sometime in the 40’s our barn had been converted to accommodate large numbers of chickens on the second floor.

Down the road from our house is a small graveyard where Marty and I plan to be buried. The headstones tell the stories of our deceased neighbors. Men lived only till their 50’s, women died earlier, often in childbirth and large families provided the labor force. On Memorial Day small flags fly from those neighbors who served in combat, some in the Civil War but most in far off places. For many of them, it was their only chance to see the world.

In the summer I walk past this graveyard several times a day on the way to our pastures. Occasionally I will pass by and see my friend Gary digging a grave. On learning that the deceased served in the Armed Forces, I will return later in dress up clothes and quietly stand behind the family. And tears will run down my face as I remember, as I relive all the reasons why I left behind my prior life and came to this small valley at the foot of the Burnt Meadow Mountains. I will look at my horses grazing in the field across from the grave yard, dried sweat from the day’s haying still on their backs. I will squeeze my hands together and wonder why I am still alive when so many died and a brew of guilt and gratitude will course through my veins.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed